Vermont's 2012 Moose Auction is Open for Bids

Always wanted a moose hunting permit but never won one in a state lottery? Here's your opportunity to bid on a permit and potentially win a hunt for Vermont's largest big game animal. Vermont's auction for five moose hunting permits is open until August 21. Sealed bids must be received by Vermont Fish & Wildlife by 4:30 p.m. that day.

Auction winners will choose to hunt in one of several wildlife management units (WMUs) open to moose hunting and choose to hunt during the October 1-7 archery season, or in the October 20-25 regular season.

The 2011 Vermont Moose Harvest Report with details on last year's hunt, including the towns where moose were taken, is on Fish and Wildlife's website. Look under "Hunting and Trapping" and then "Big Game."

During the regular season, you will be able to name a partner to hunt with you, who also may carry a firearm or bow, and a third unarmed person may accompany you on your hunt. There are many experienced Vermont moose hunting guides who could assist you if needed.

Bids do not include the cost of a hunting license (residents $22, nonresidents $100) or moose hunting permit fee ($100 for residents and $350 for nonresidents). The bid amount and moose hunting permit fee must be paid by September 6.

Contact the Vermont Fish & Wildlife Department to receive a moose permit bid kit. Telephone 802-241-3700 or email (fwinformation@state.vt.us).

Proceeds from the moose hunting permit auction help fund Vermont Fish and Wildlife educational programs. Winning bids are typically at least $4,000.Contact:

Cedric Alexander, 802-751-0105; Mark Scott, 802-241-3700

Showing posts with label moose hunting. Show all posts

Showing posts with label moose hunting. Show all posts

Thursday, July 12, 2012

Vermont's 2012 Moose Auction is Open for Bids

for you moose hunters out there

Tuesday, January 27, 2009

Wednesday, May 28, 2008

Moose, ADKs, and Cornell alum scientists

Moose Gain Ground but Keep a Low Profile

By LISA W. FODERARO McKENZIE

MOUNTAIN WILDERNESS, N.Y.

From the New York Times

Here in the boreal forests of the Adirondack Mountains, moose are seemingly everywhere and nowhere.

In the sachet-scented gift shops of Lake Placid, where high heels outnumber hiking boots, there are moose-inspired cookie jars, moose-shaped soaps, moose-head lollipops, moose-emblazoned kitchen mitts and a $12.95 book titled “Uses for Mooses and Other (Silly) Observations.”

But while it may be the overworked mascot of the Adirondacks tourist trade, the moose, which has quietly returned to northern New York over the last quarter-century, remains a mystery. Many longtime residents have never glimpsed one. And wildlife biologists are unsure whether the small but secure population of some 400 moose is on the verge of an explosion — as happened in New Hampshire in recent decades — or headed for an eventual decline because of global warming.

“It’s the icon of the north woods,” said Heidi E. Kretser, a scientist with the Wildlife Conservation Society, the nonprofit organization that operates the Bronx Zoo and has an outpost in the Adirondacks. “They’re massive creatures. They’re just very appealing characters.”

To better understand their lifestyle and behavior, the Wildlife Conservation Society sent specially trained dogs into the piney woods here recently, not in search of actual moose, but their scat, or excrement. One morning this month, Camas, a German shepherd who had traveled from Montana for the mission, traversed the dense wilderness around Moose Pond. The forest floor was just springing to life, with wood sorrel and striped maple saplings pushing up through dead leaves and ferns unfurling.

But in a sign of moose elusiveness, Camas found the scat of black bear and ruffed grouse but nothing redolent of moose, even though there had been recent sightings in the area. (The day before, a colleague of Camas had more luck, sniffing out nine discrete examples of moose scat; the conservationists organized 20 such outings between May 12 and May 25, in a program financed in part by the Natural History Museum of the Adirondacks, popularly known as the Wild Center, in nearby Tupper Lake.)

By analyzing the scat, the society hopes to learn more about the habits, genetics and overall health of New York’s moose population.

But with only a few hundred moose scattered across the Adirondack state park, which comprises private and public lands in an area roughly the size of Vermont, locating moose scat is far easier than locating the actual mammals, despite their hulking size. (Bull moose can weigh up to 1,400 pounds and eat 40 to 60 pounds of vegetation a day.)

Scat analysis is less traumatic for moose than more traditional techniques. “It’s not a replacement for collaring, but it’s another tool for managers and researchers and it’s noninvasive,” Dr. Kretser said. “You eliminate the stress of darting the animal.”

Moose were hunted out of existence in the Adirondacks just before the Civil War, but began to tromp back into the state in the early 1980s, entering from Vermont and Canada. Wildlife experts expect their numbers to continue to climb, but they also speculate that the moose, which rely on birch twigs, maple bark and other vegetation found in northern hardwood forests, could eventually retreat. The animals could leave the Adirondacks for points farther north, after decades of global warming.

“We’ll see the population double in size,” said Chuck Dente, a big-game biologist for the State Department of Environmental Conservation, noting that Vermont and New Hampshire each have several thousand moose. “The more moose you have, the more they can reproduce very quickly and successfully.

Once they get established, the population can take off. But what happens after that, we don’t know. We have a group of scientists working on the ramifications of climate change.”

Recent moose necropsies — the equivalent of autopsies — have revealed that a parasite called brain worm is taking a toll on moose here. The worm gets into the brain cavity and the spinal column and ultimately kills the moose.

Mr. Dente said that rising temperatures in the coming decades could lead to more brain worm, which is part of a complex food chain involving snails, as well as other parasites. “As things warm up a little bit, that allows the snail to survive better,” he said.

Whereas black bears, which number about 5,000 in the Adirondacks, are considered a nuisance by some, foraging for garbage, moose pretty much keep to themselves. If their numbers grow, however, so will the possibility of moose-vehicle collisions, and state officials and wildlife advocates are girding for a backlash in public perception.

In New Hampshire, which is home to about 6,000 moose, there are 200 to 250 collisions involving moose each year. Human fatalities are rare, but there have been serious injuries.

By contrast, Adirondack Park, which contains virtually all the moose in New York State, has an average of four to six collisions a year, and none so far, environmental officials say, have been fatal to the drivers.

Several weeks ago in Saranac Lake, for instance, a moose was killed after being struck by three vehicles in a row.

“Hitting a moose is a nasty thing because you really don’t see them,” Mr.

Dente said. “They’re a solid color at night, and they’re so tall that you don’t get the reflections of their eyes from the headlights. You don’t see them until you’re right on top of them.”

For now, their presence in the Adirondacks is more a source of fascination than vexation. “The moose are kind of mysterious,” said Julie Outcalt, a sales clerk at the Adirondack Museum store on Main Street in downtown Lake Placid, where shoppers can choose among moose-head bookends ($130) and a birch-bark moose figure ($42). “I’ve been here 30 years, and I’ve never seen one.”

Moose are not listed as endangered or threatened in New York, but they are protected, which means they are off limits to hunting. Maine, Vermont and New Hampshire allow limited moose hunting. “If all of a sudden we got up to 800 or 1,000 moose, we would start to seriously look at hunting permits,” Mr. Dente said. “Or if we saw a lot of roadkill, we might make that the only area you could hunt in.”

That’s fine with many environmentalists, who point out that moose have no natural predators and that fees from hunting licenses help pay for wildlife conservation efforts. “You want the moose population to be at a level where there’s not a lot of negative interactions with people,” said Dr. Kretser of the conservation society.

Bushwacking her way through here, close on the heels of Camas, the German shepherd, Dr. Kretser said she hoped moose would remain a fixture of the Adirondack woods — and not merely raw material for trinkets.

“The Adirondacks is a boreal area, and many of the boreal species, including moose, loons, gray jays and rusty blackbirds, are at the southern extent of their range,” she said, climbing over a moss-covered log. “If climate change accelerates, as people are predicting, then moose will have a tough time.”

By LISA W. FODERARO McKENZIE

MOUNTAIN WILDERNESS, N.Y.

From the New York Times

Here in the boreal forests of the Adirondack Mountains, moose are seemingly everywhere and nowhere.

In the sachet-scented gift shops of Lake Placid, where high heels outnumber hiking boots, there are moose-inspired cookie jars, moose-shaped soaps, moose-head lollipops, moose-emblazoned kitchen mitts and a $12.95 book titled “Uses for Mooses and Other (Silly) Observations.”

But while it may be the overworked mascot of the Adirondacks tourist trade, the moose, which has quietly returned to northern New York over the last quarter-century, remains a mystery. Many longtime residents have never glimpsed one. And wildlife biologists are unsure whether the small but secure population of some 400 moose is on the verge of an explosion — as happened in New Hampshire in recent decades — or headed for an eventual decline because of global warming.

“It’s the icon of the north woods,” said Heidi E. Kretser, a scientist with the Wildlife Conservation Society, the nonprofit organization that operates the Bronx Zoo and has an outpost in the Adirondacks. “They’re massive creatures. They’re just very appealing characters.”

To better understand their lifestyle and behavior, the Wildlife Conservation Society sent specially trained dogs into the piney woods here recently, not in search of actual moose, but their scat, or excrement. One morning this month, Camas, a German shepherd who had traveled from Montana for the mission, traversed the dense wilderness around Moose Pond. The forest floor was just springing to life, with wood sorrel and striped maple saplings pushing up through dead leaves and ferns unfurling.

But in a sign of moose elusiveness, Camas found the scat of black bear and ruffed grouse but nothing redolent of moose, even though there had been recent sightings in the area. (The day before, a colleague of Camas had more luck, sniffing out nine discrete examples of moose scat; the conservationists organized 20 such outings between May 12 and May 25, in a program financed in part by the Natural History Museum of the Adirondacks, popularly known as the Wild Center, in nearby Tupper Lake.)

By analyzing the scat, the society hopes to learn more about the habits, genetics and overall health of New York’s moose population.

But with only a few hundred moose scattered across the Adirondack state park, which comprises private and public lands in an area roughly the size of Vermont, locating moose scat is far easier than locating the actual mammals, despite their hulking size. (Bull moose can weigh up to 1,400 pounds and eat 40 to 60 pounds of vegetation a day.)

Scat analysis is less traumatic for moose than more traditional techniques. “It’s not a replacement for collaring, but it’s another tool for managers and researchers and it’s noninvasive,” Dr. Kretser said. “You eliminate the stress of darting the animal.”

Moose were hunted out of existence in the Adirondacks just before the Civil War, but began to tromp back into the state in the early 1980s, entering from Vermont and Canada. Wildlife experts expect their numbers to continue to climb, but they also speculate that the moose, which rely on birch twigs, maple bark and other vegetation found in northern hardwood forests, could eventually retreat. The animals could leave the Adirondacks for points farther north, after decades of global warming.

“We’ll see the population double in size,” said Chuck Dente, a big-game biologist for the State Department of Environmental Conservation, noting that Vermont and New Hampshire each have several thousand moose. “The more moose you have, the more they can reproduce very quickly and successfully.

Once they get established, the population can take off. But what happens after that, we don’t know. We have a group of scientists working on the ramifications of climate change.”

Recent moose necropsies — the equivalent of autopsies — have revealed that a parasite called brain worm is taking a toll on moose here. The worm gets into the brain cavity and the spinal column and ultimately kills the moose.

Mr. Dente said that rising temperatures in the coming decades could lead to more brain worm, which is part of a complex food chain involving snails, as well as other parasites. “As things warm up a little bit, that allows the snail to survive better,” he said.

Whereas black bears, which number about 5,000 in the Adirondacks, are considered a nuisance by some, foraging for garbage, moose pretty much keep to themselves. If their numbers grow, however, so will the possibility of moose-vehicle collisions, and state officials and wildlife advocates are girding for a backlash in public perception.

In New Hampshire, which is home to about 6,000 moose, there are 200 to 250 collisions involving moose each year. Human fatalities are rare, but there have been serious injuries.

By contrast, Adirondack Park, which contains virtually all the moose in New York State, has an average of four to six collisions a year, and none so far, environmental officials say, have been fatal to the drivers.

Several weeks ago in Saranac Lake, for instance, a moose was killed after being struck by three vehicles in a row.

“Hitting a moose is a nasty thing because you really don’t see them,” Mr.

Dente said. “They’re a solid color at night, and they’re so tall that you don’t get the reflections of their eyes from the headlights. You don’t see them until you’re right on top of them.”

For now, their presence in the Adirondacks is more a source of fascination than vexation. “The moose are kind of mysterious,” said Julie Outcalt, a sales clerk at the Adirondack Museum store on Main Street in downtown Lake Placid, where shoppers can choose among moose-head bookends ($130) and a birch-bark moose figure ($42). “I’ve been here 30 years, and I’ve never seen one.”

Moose are not listed as endangered or threatened in New York, but they are protected, which means they are off limits to hunting. Maine, Vermont and New Hampshire allow limited moose hunting. “If all of a sudden we got up to 800 or 1,000 moose, we would start to seriously look at hunting permits,” Mr. Dente said. “Or if we saw a lot of roadkill, we might make that the only area you could hunt in.”

That’s fine with many environmentalists, who point out that moose have no natural predators and that fees from hunting licenses help pay for wildlife conservation efforts. “You want the moose population to be at a level where there’s not a lot of negative interactions with people,” said Dr. Kretser of the conservation society.

Bushwacking her way through here, close on the heels of Camas, the German shepherd, Dr. Kretser said she hoped moose would remain a fixture of the Adirondack woods — and not merely raw material for trinkets.

“The Adirondacks is a boreal area, and many of the boreal species, including moose, loons, gray jays and rusty blackbirds, are at the southern extent of their range,” she said, climbing over a moss-covered log. “If climate change accelerates, as people are predicting, then moose will have a tough time.”

Labels:

Adirondacks,

Cornell,

moose,

moose hunting

Friday, January 20, 2006

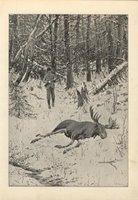

Heroes of Sporting Art: Pathwalking Moose Hunter

Hey gang,

Hey gang,Once again it is time for another installment in our "Heroes of Sporting Art" series of postings. Today we have A. B. Frost returning with a print of "Pathwalker and the Moose." As you can see at right, here our hero PW is walking down the path to the moose he has just slain with what looks to be a Winchester repeater. (Newsflash this week: Winchester will no longer be making guns in its New Haven, Connecticut plant after they close the plant later this year.)

I ran across the following film footage of a newscast about Vermont moose hunting. The short 4 minute film can be viewed with either QuicTime or Windows Media Player 9.

For folks who can't get enough A.B. Frost, here is a closeup detail of the moose hunter print. PW, it looks like your hands are cold without gloves--and how do you get the moose out of the woods, anyway?

Friday, December 30, 2005

Homage to Path Walker, Part Trois

Here's my favorite recipe for jellied moose nose. Enjoy.

Here's my favorite recipe for jellied moose nose. Enjoy.Jellied Moose Nose

1 upper jawbone of a moose

1 tsp. salt

1 onion, sliced

1/2 tsp. pepper

1 clove garlic

1/4 cup vinegar

1 Tbs. mixed pickling spice

Cut the upper jaw bone of the moose just below the eyes. Place in a large kettle of scalding water and boil for 45 minutes. Remove and chill in cold water.

Pull out all the hairs - these will have been loosened by the boiling and should come out easily (like plucking a duck). Wash thoroughly until no hairs remain.

Place the nose in a kettle and cover with fresh water. Add onion, garlic, spices and vinegar Bring to a boil, then reduce heat and simmer until the meat is tender. Let cool overnight in the liquid.

When cool, take the meat out of the broth, and remove and discard the bones and the cartilage. You will have two kinds of meat, white meat from the bulb of the nose, and thin strips of dark meat from along the bones and jowls.

Slice the meat thinly and alternate layers of white and dark meat in a loaf pan.

Reheat the broth to boiling, then pour the broth over the meat in the loaf pan.

Let cool until jelly has set. Slice and serve cold.

courtesy of recipecottage.com

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)